5 quirks of customer behaviour that it pays for retailers to understand

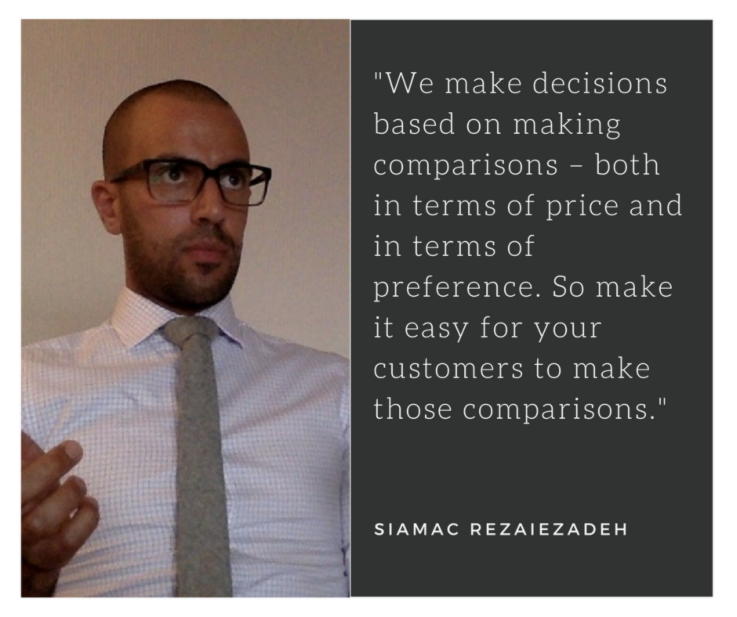

Siamac Rezaiezadeh of Ancrath explains how an understanding of customer behaviour can help retailers be more successful

Humans don’t always make rational decisions. We exhibit a range of quirks in our behaviour that sometimes mean we act irrationally, at least in the economic sense. As a retailer, it pays to know what some of these quirks, or cognitive biases, are and why you should understand them.

Here are five that can be crucial to success:

The Authority Bias

What is it?

Humans have a tendency to attribute greater weight and accuracy to the opinion of an authority figure. Think of it as a time-saving, decision-making device that has many, many benefits. In our societies, doctors, police officers, professors (and so on) all hold a position that gives them authority and we tend to do what they tell us to do. The most powerful people in the world, be they Presidents, Prime Ministers or corporate CEOs, will take off their trousers and sit on a cold table if a doctor tells them to.

This tendency is deep-seated in us and makes sense: an accepted system of authority enables cultures to develop, more easily enabling resource allocation, trade, society, family, defence and expansion. It is also part of the package that enables learning and the development of new ideas. As a decision-making shortcut, the Authority Bias can be phenomenally useful (do as the doctor says, or spend 10 years learning yourself, by which time the information is going to be way too late).

So what?

There is an opportunity for retailers to set themselves up as experts in areas related to their products and services. The potential here is not just to consider ourselves as expert retailers, but also as experts in how best to use the products and services we offer. This means offering services that demonstrate the retailer’s expertise and at the same time empowering staff to become experts in their chosen fields too. By way of example, why not offer clear food and wine pairing choices if you are selling food and drink? Or display placards of fitness instructors offering advice in a shop selling sporting goods?

Relative Advantage

What is it?

Humans struggle to make absolute judgements about products – we find it much easier to judge a product if we can judge its benefits relative to something else. Faced with two options with difficult to compare attributes (A and B), humans struggle to reach a decision or decide to play it safe and go with something already known or nothing at all.

Alternatively, faced with three options, A, B and B’ (where B’ is an ever so slightly worse version of B), B will overwhelmingly be the choice we make – because we were given something to compare B to. From real estate to dating, this works. (Potential cautionary tale – next time your ever so slightly more attractive friend asks you to be his or her “wingman”, have a think about why…)

So what?

The Relative Advantage has important implications across a number of areas that retailers should be aware of, but the clearest is when it comes to pricing.

The price of a product in isolation is a difficult attribute for your buyer to judge – is it good value? Am I getting a good deal? In absolute terms these are difficult questions to answer.

However, comparing one price relative to another price is an easier task. Driving buying decisions towards a choice that is most beneficial for you, the retailer, is made easier if you load value into an offer (which is good for the client) AND by presenting a similar offer that doesn’t contain as much value – thereby effectively simplifying a comparison of the two offers and making it easy to identify the better choice. Remember the key here is enabling a straightforward comparison between options with similar attributes.

There are also important lessons to learn when it comes to introducing new products or services. Innovation is great, but when presenting a new product remember that humans look for easy comparisons. In a choice between option A, option B and option B’ (again, where B’ is a slightly worse version of B), the easiest choice is for the buyer to go with option B because option A does not have easily comparable attributes. So rather than presenting yourself as something completely new, try presenting yourself as a great improvement on an existing market of products – especially when you are up against competition.

We make decisions based on making comparisons – both in terms of price and in terms of preference. So make it easy for your customers to make those comparisons.

The Zeigarnik Effect

What is it?

People have a tendency to remember unfinished or interrupted tasks better than those they have completed. In essence, we like to finish what we have started. I like to think of it as an open mental to-do list. If something is left open or unresolved in our mind, a certain amount of mental tension keeps it prominent in our memory. When the task is finally completed, the tension is released and we can move on. The Zeigarnik Effect is used to great effect in the entertainment sector, where TV (and book, and film franchise) cliffhangers keep the audience primed and anxiously anticipating the next instalment.

So what?

In a retail environment, think of the potential the Zeigarnik Effect could have, particularly when it comes to creating or enabling customer loyalty, engagement and repeat purchases. We tend to view a customer interaction as a single event with a start and a finish (i.e. a one-time purchase) – but there is an argument that it doesn’t have to (and shouldn’t) be this way. Think about ways you can keep the retail loop open with customers.

For example, if a product is unavailable right now, the customer can be alerted as to when the item is back in stock – but how about taking it a step further? Tell the customer right then and there when it will be back in stock and when they can come back to collect it – potentially even taking payment in advance. That keeps the loop open, bringing the customer back in for another store visit. Marketing information should also lead the customer into the next part of the story: if you want to encourage feedback, let the customer know that they will receive a request for feedback in the near future – that way the experience is not yet fully closed.

Choice-Supportive Bias

What is it?

Humans have a tendency to remember the decisions they made as having more positive attributes than may have actually been the case, and conversely, we remember the options not chosen more negatively than they were. A cynic might even phrase it in this way: “I just spent £500 on this new phone, therefore it must be a good one as I wouldn’t have made that decision if it wasn’t.”

Think of the Choice-Supportive Bias as a mental safety mechanism: consider that humans often say to themselves: “I chose this option; therefore it must have been the best option.” In doing so, it helps reduce regret and generally promotes well-being. Imagine being constantly plagued by doubt over every single decision you ever made; your ability to make future decisions would most likely be severely impaired, particularly under pressure.

So what?

There are two important points for retailers to consider here. The first is that when trying to get a customer to change their mind about something (i.e. ditch their old product and buy yours instead), consider the fact that they will remember, probably fondly, the existing decision they made – and it will look like the right decision to them. There is little use trying to position the old decision as a poor choice as it just won’t match up with how they remember it. Don’t try to change their mind, instead focus on accepting that their previous decision was a good one, but now the environment has changed and it is time to make a new decision.

The other point to consider is about your own decisions. Take a look at what you are doing today across your business and ask yourself this: “Were the decisions we made truly the right ones, or am I just remembering them fondly to preserve my own sanity?”

Social Proof

What is it?

Looking for and accepting social proof is a phenomenon whereby the probability of someone adopting a belief, idea, fad or trend increases the more that that it has been already taken up by others. And it isn’t necessarily a bad thing – like many cognitive biases, it certainly isn’t always a bad rule of thumb.

Let’s say that you are visiting a small town in France for the first time on holiday and you come across two restaurants. Your stomach rumbles so you know it’s time to eat. How do you choose which one to go to?

If you happen to be a food expert, with a high level of knowledge of French cooking, you would take a look at the menus, find out about the chefs, judge the quality of service based on what you can see and probably take in a few other factors that the average person would not even be aware of. However, if you don’t have an intimate knowledge of haute cuisine, you will probably choose whichever one looks the busiest, the most popular one.

The reality is that most people aren’t experts in every field and so copy the choices that other people make.

So what?

The opportunities for learning and execution here are huge for retailers – and I don’t see them being taken up to the fullest. One question that should always be asked is “how can I demonstrate that others are already doing this?” Is it possible to show how many people have made similar purchases or decisions today? This month?This year?Can you further qualify those decisions by stating that not only people, but also people just like you, have made those same decisions?

Online retailers do well to use reviews as ways of demonstrating social proof, but let’s take it further: Can I boast about how many people purchased this today? How about labelling the top selling brand or item in store to show a clear measure of popularity?

Social proof is about making a decision easier, and less risky, by making it obvious that other people have already made that same decision.

The five quirks described here are important, but they really are the tip of the iceberg. Understanding how and why our customers behave the way they do and then altering our own behaviours as a result can bring about stronger, more valuable, customer-retailer relationships, and can even help customers make smarter purchasing decisions.