How HOT:SECOND brought digital fashion into physical retail

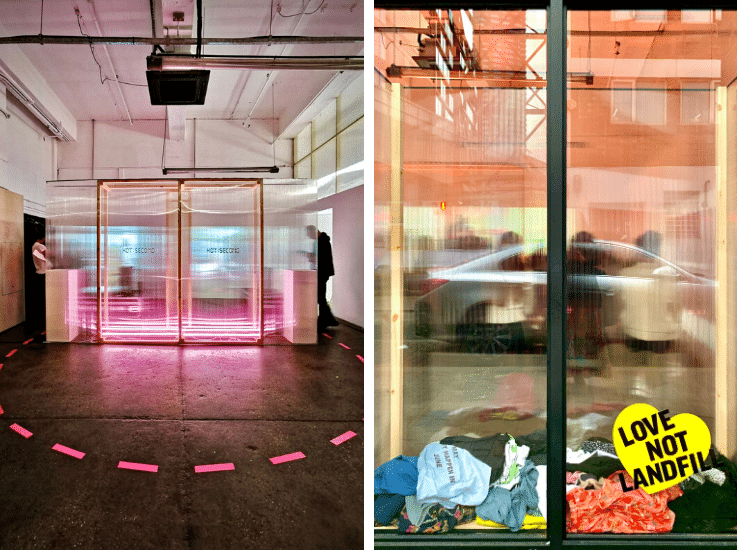

Last month an innovative new retail space popped up in London’s Shoreditch. Billed as a ‘world first circular economy concept store’, HOT:SECOND was a space that invited customers to trade physical products for a digital fashion experience.

By bringing in an unloved garment, rather than throwing it out, visitors had the chance to try on a digital fashion garment from leading brands like The Fabricant, Carlings/VIRTUE and RÆBURN. The hope was that by combining physical retail and digital products a new type of fashion experience could be offered.

HOT:SECOND also hopes to change perceptions around digital fashion by giving curious fashion fans the chance to explore it for themselves.

We spoke to HOT:SECOND founder and academic Karinna Nobbs to find out what was behind the concept, what the future holds for digital fashion and what the next iteration of the HOT:SECOND looks like.

Karinna Nobbs, Founder, HOT:SECOND

What is HOT:SECOND?

HOT:SECOND is an experimental retail concept focused on the evolving and early field of digital fashion garments.

The initial premise of what I wanted to do was to look at how could we ask people to exchange garments that they don’t want anymore, or to customise something that they currently don’t love, and use that as a currency to try a digital fashion experience.

The reason behind this is that everybody I asked, in the fashion sector and the general public, about ‘what’s your take on digital fashion’ scratched their heads. I got excited because I feel like this is such a new space.

What I wanted to do with the HOT:SECOND pop-up store was to try to demystify the concept a little bit and try and make it accessible. I wanted to make the barriers to entry low and to get people to try it.

Why did you decide to open a physical space?

One of the reasons that I was super keen to do it in a physical context first is that my background when I first started out in fashion was as a visual merchandiser. I’m very passionate about how this kind of sensory experience and the environment can shape your attitudes and behaviours and emotions and all that kind of stuff.

Also, because it was so new, I felt like guiding people through the experience. I wanted to have the balance of human and digital not necessarily even, but close.

How did the process work?

The store window display was an installation by Love not Landfill and we asked people to drop their garments into there. As a result of that, it kind of looked like landfill in the window. Again, I want people to have that kind of emotional trigger and be like ‘oh yeah, this is the thing that I’m doing, and this is the reason why I’m doing it’.

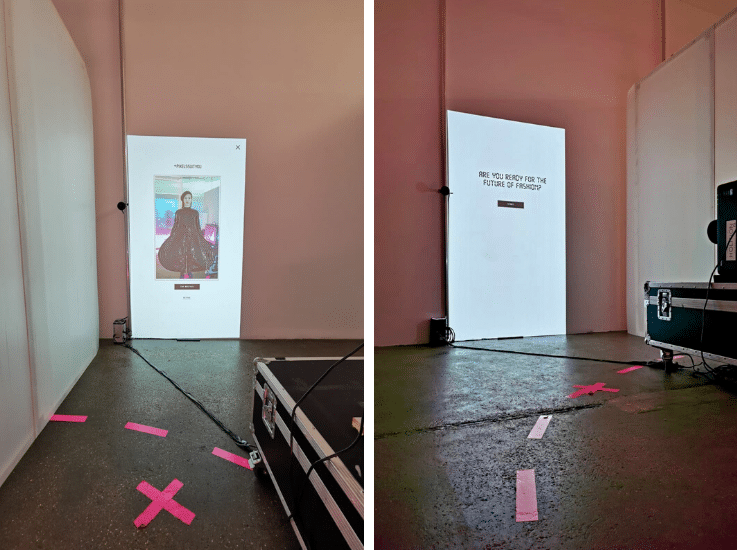

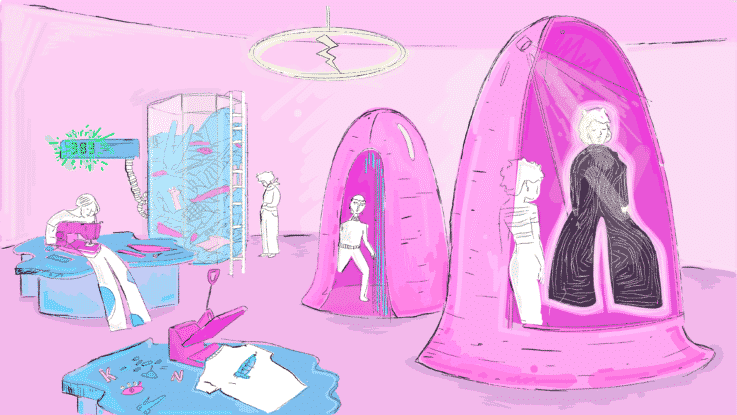

In the space we had two pods with a projector, a camera and a computer inside. When you walked in, first of all there was a screen that said, ‘do you want to experience the future of fashion?’

Inside the pod with the visitor was either myself or one of the people who were working with me in the store, which were mostly interns from the various universities that I teach at.

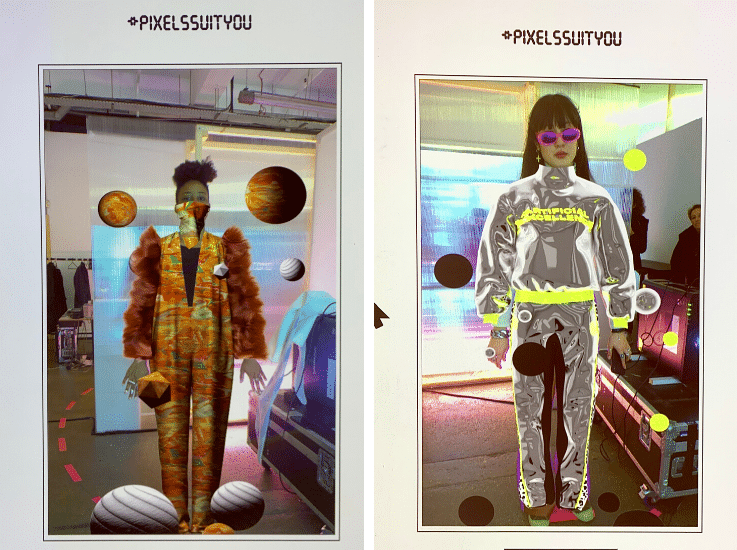

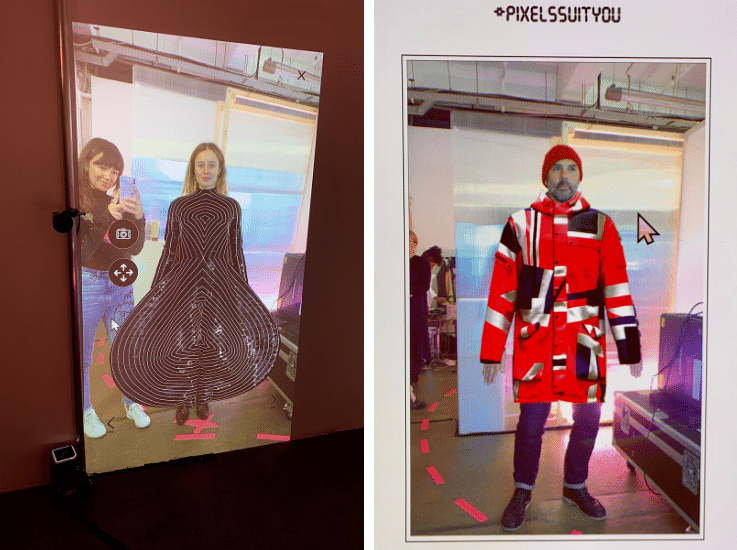

We then talked people through the four garments that were in the experience and then they were able to try one on. I use try very lightly because it was a static try-on experience, so the digital garment didn’t move in itself. We did have some animation with some of them like The Fabricant piece.

We attached the digital garment to the person in a very manual way. We asked the person to stand quite still and then we lined up where their body was and took a photograph. That was the mechanics.

Did the customer get anything to take away?

The master plan was that they got emailed their photograph and that I printed out the photograph, but we didn’t manage to get the printer set up. So, I asked people to message me on Instagram with the time they were there and then I would send them their image. I really wanted to have that physical and digital take away, but we just didn’t quite manage to truly do it for the first one.

Who did the digital garments come from?

I knew I wanted to get The Fabricant and Carlings because any digital fashion article anywhere references them as the pioneers. I was really excited when they both said yes right away.

The third person I wanted to contact was Christopher Raeburn, because one, I wanted to choose a London based designer, and two, I wanted to choose someone who already had a customer base and an openness to using innovation to look at the connections between innovation and sustainability. Again, they were really open and excited to be involved because it was very new for them as well.

When I was doing my research for HOT:SECOND, I asked people ‘if you were going to try digital fashion for the first time, what type would you want to try?’ Almost 50% of people said they wanted to try a luxury brand.

I think that does signal something as to where the demand is in the marketplace. I was using The Fabricant as the luxury version, but actually the parka that was the Christopher Raeburn garment is actually the most expensive piece in his collection. I chose it because it’s kind of iconic and the design was very striking as well.

One of the other things that came through when I asked consumers ‘what type of garment did you want to try’ was iconic pieces from history or costumes. I’m super passionate about vintage and I see that a potential use case for digital fashion going forward is to have access to historical pieces. I really wanted to do, for example, a Biba piece in the collection, but I didn’t manage to organise it for this one. But things that people don’t generally have access to or things that evoke memories or emotions, I think digital fashion could be really powerful for.

How did people respond to the concept when they were in space?

They were very receptive. If I compare it to the people asked in a survey cold, there was definitely more apprehension, curiosity and skepticism there. In the actual experience, people just thought it was fun, even though the tech was rudimentary and quite underdeveloped.

It almost sparked them off to think about ‘well actually if it did this to me and if it did that and if there was music and if there was mirrors all around and if I could make a gif out of it, I would love to do that’. They were way more enthusiastic than I had even anticipated.

Is there anything else you learnt from operating the space or anything you’d do differently knowing what you do now?

I had a target to save 500 garments from landfill. I think I only have around half that, although I would say between 75 and 100 people customised things. I had wanted to create an animated asset and also have more instructions and more people within the store.

Sometimes I was the only person in the store or maybe I had two people helping me, but we had 25+ people in the store. Having more people to be able to educate consumers on the experience would be something I would do differently.

More pre-marketing to try and really drive that message home about the link between leaving the garment and using that as a currency is something else that I would have tried to address. It was a bit like reverse psychology in some ways. I know the word disruptive is very overused, but it was a non-traditional path that I was interested in.

What particular challenges are there around the future of digital fashion?

It’s an uphill journey. The number of times I’ve seen the mainstream media describe it as the Emperor’s New Clothes, so we have to battle against that. That is one perspective of how it could be viewed. But actually, there is the sustainability angle there as well.

The other reason I really wanted to do this, and it relates back to again being a visual merchandiser, is that I don’t love the narrative that we see in the media that you should feel guilty about liking or enjoying fashion. I understand that the fashion industry is a massive polluter and we need to educate people about their consumer behavior, but that’s another reason that I think digital fashion could to be a way to enjoy fashion with less guilt.

Also, the tech isn’t perfect yet. It’s still going to be at least 18 months until the trying on element is where it needs to. There are so many people try to solve this issue. That’s not really a road I want to go down.

I’m more about experience and the fun and theatre and just getting a feel for whether or not this is about a garment that exists in real life or if it is more about connecting with brands on a more emotional or relationship level. Christopher Raeburn is interested to see how this experience could maybe live on in the Raeburn Lab so people have access to archive pieces.

The other challenges are if a consumer buys a digital asset and they’re non-technical if you like what do they do with it? It just sits on their computer. At the moment there’s almost a gap for a service provider.

One of the issues that, for instance, Carlings had with their collection was that they could only digitally tailor a small number of items per day because it was so time intensive for a creative to attach the digital garment or superimpose it to the picture of the consumer.

The other thing is where do we wear our digital clothes? If you aren’t wearing them on an avatar and you’re just wearing them on yourself, now it is only social media. But Second Life is making a comeback. The Fabricant is about to release a new platform as well where you’ll be able to wear digital clothes. They’re starting to open up. I think it would be wonderful in the future for games or platforms if there was a universal asset. If I bought something from Nike can I wear it in Fortnite, can I wear it in Second Life, can I wear it in augmented reality glasses experiences?

To all C-suite leaders, I’d say do you have a digital fashion strategy for 2020? If not, why not?

What do you have planned next?

We’re going to be bringing the experience to Berlin in January. It’s likely to be quite a close replica of what I did in London but maybe with one different garment and a refinement of the experience.

I’m doing it in partnership with Lukso, the blockchain company, so we’re looking at what could we sell and what could we talk around and what’s digestible for consumers.

The other thing I want to do next is to try and be the first retailer that sells a digital garment on the blockchain. It’s similar to what The Fabricant did, but at a lower price point. Also, with The Fabricant and Carlings the money for both of those sales went to charity. I would like to try and be the first person where the money goes to the person who created the garment.

The only way that digital fashion can be commercialised is if you somehow authenticate the assets that you have because it protects the brand and the consumer as well.

It’s going to be slow increments because of the technology. I’m just trying to get more insight because of my background as an academic. I just want to try and use this to share and learn to help make the fashion process fun, but in a way that essentially makes sure we’re still here in the future.

Images courtesy of HOT:SECOND

If you’re interested in learning more about HOT:SECOND or about what digital fashion might mean for your business, get in touch with Karinna at Holler [at] a-hot-second [DOT] com.

Want to go straight to the hottest retail technologies, latest disruptive thinking and simplest new ways to lower costs and boost sales?

Transform your team’s thinking using Insider Trends’ little black book. Find out how here.