How Azoya is helping overseas brands to succeed at ecom in China

China is much talked about in the retail world as a place of opportunity for brands. It is, after all, on the cusp of being the biggest consumer market in the world.

Yet, across all sorts of industries big names from the West have found that success in the country is not a simple task. Many fall foul of thinking about China in the same way that they do other countries they operate in when in reality it is very much its own beast.

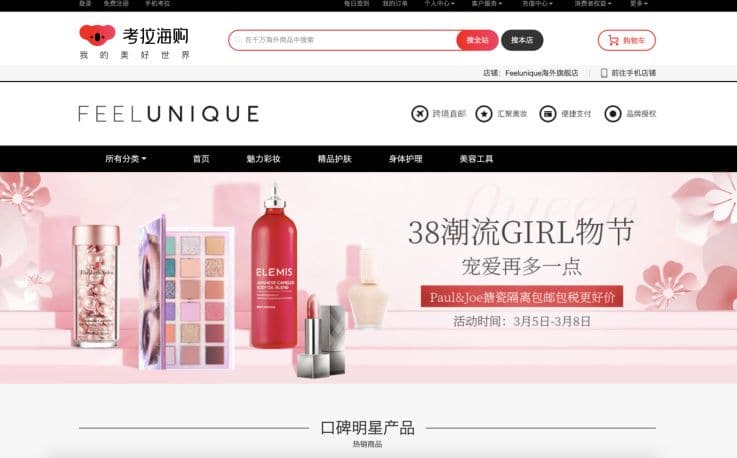

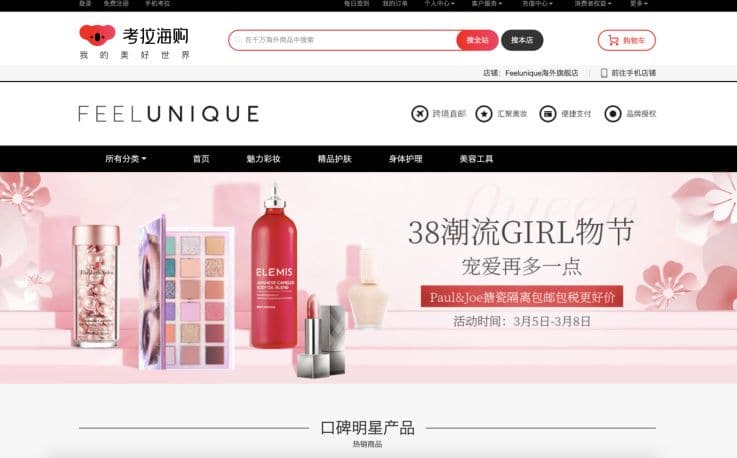

Azoya is working to help retailers and brands to make their move into China the right way. An enabler of cross border ecommerce, it acts as valuable partner in helping them navigate this new market in a locally minded way. It’s an approach that equals ecommerce success.

We spoke to Azoya’s European MD Elena Gatti to find out how Azoya helps brands navigate market differences, where most go wrong and how Chinese retail is innovating at a rapid pace.

Elena Gatti, Managing Director, Europe, Azoya

Can you describe Azoya in a nutshell?

Azoya is a cross border ecommerce enabler for brands and retailers from all over the world who are looking to access the Chinese market.

There are a lot of challenges when trying to enter this market; it’s a completely different world. Retailers need to have a local partner in the country as not only is the customer different but so are the Chinese ecosystem and the internet landscape.

Azoya is a strong partner to these brands and retailers, sitting close to the customers in China.

We can be viewed as an enabler, not only helping them build the website but also operating it and doing campaigns. We have a collection of 50 different APIs with marketing channels, shopping guides, blogs, etc; so we can spread and push digital marketing to drive traffic to the web shops.

Azoya was founded five years ago, as a Chinese company based in Shenzhen. We have around 250 employees, most of them in mainland China. The rest are spread out all over the world (in Germany, UK, Australia, Japan etc), mainly for business development and project coordination.

We specialise in the categories of beauty, nutrition, accessories, OTC, and pharma; i.e. industries that can ship small and low value items.

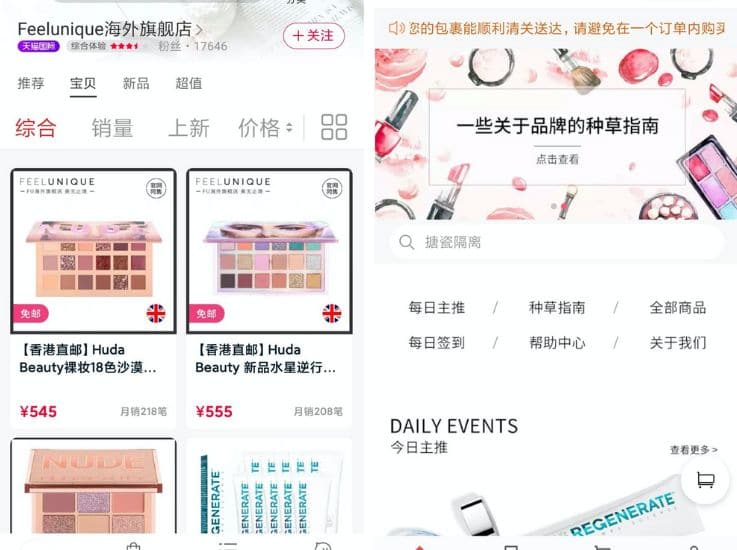

What is the business model in terms of logistics?

With cross border ecommerce, the safest way to start is with a drop-shipping model; i.e. the company packs the parcels in their home country and sends them directly to China. The issue with that is the poor customer experience, as you would need to target customers who would be willing to wait 10 to 14 days for their items to arrive.

We do operate a warehouse in Hong Kong which is available to some of our partners, but it has to be a controllable risk. When starting out with a new brand we usually use drop-shipping. The warehouse would be a second step, when the brand gets more experienced and has a couple of years of customer knowledge.

How much does omnichannel feature in your work?

Omnichannel is not a topic of discussion in China. It just exists, it’s everywhere.

There are mini programs available on WeChat where you can build your store in less than a day and have it linked. Customers can place an online order straight away and even pay directly via this mini program without having to enter their credit card number, as everything is connected.

These WeChat programs also offer a link to the customers’ friend network, allowing them to send across the latest product they bought, which that friend can then buy with just two small clicks.

The process is much more difficult in the West. You would have to create a particular app for your store, convince your customers to download it amongst millions of other apps, and at the same time make sure that customer can still find you from a desktop.

Azoya is only an online channel for the moment. We have done some pop-up stores for a few brands but to go offline and open a retail store in China would require a lot of investment, a lot of time, and a lot of bureaucracy. The company would need to have a Chinese entity, the products would all have to be registered etc. Of course, we would help our partners should they wish to do so at some point, but for the moment everyone seems happy with cross border selling.

What type of consumers do you target?

At the moment we focus solely on tier one and tier two cities. There are two main reasons for that. As cross border ecommerce, we are selling products that are being shipped from overseas, so they are firstly more expensive than domestic ones, and secondly, they take longer to arrive.

This means that we are targeting a particular type of consumer who is consciously choosing to buy cross border, who is trusting that that brand is exactly what they are looking for; and who is willing to wait that long. That type of customer is typically very educated, in an office job, earning a middle to high class income and mainly live in tier one and tier two cities.

But we are seeing an interesting trend coming out of tier three and tier four cities; the consumer power seems to be increasing. We hope that in a few years we will be able to find cross border shoppers over there.

How focused are Chinese consumers on international brands?

If you look at four or five years ago, Chinese customers were moving away from Chinese brands and looking at international ones as they trusted them more on quality (think about the baby milk scandal for example). But now the focus has changed, Chinese consumers are realising that the domestic brands are actually good, and they are cheaper.

These brands are not only fast to adjust to new channels, they are also becoming increasingly creative. A good example of that is The Forbidden City in Beijing which has founded a very successful beauty brand with high quality premium products that makes customers proud to buy local.

What are the biggest mistakes you have seen retailers make when trying to enter the Chinese market?

The biggest mistake most brands make is that they just duplicate what they did in their home country, apply it as is to the Chinese market and think they will experience the same amount of success. It’s a mindset of many Western countries to assume that they can use the same roadmap, maybe just changing the name on social media – not taking into account that the customers are different.

Very few brands will take the time to really understand the specific needs and wants of the country and figure out how they can answer them. They only see the numbers, the potential 1.4 billion customers. What they forget is that the Chinese customer already has access to products from all over the world, not only from Europe but also from Australia, Japan, Korea, etc. And that’s without mentioning the strong domestic brands.

These Western brands should take the time to think about their unique selling point and what would make that customer buy their product instead. They should understand the culture and listen to the target groups. This is the normal process retailers go through when trying to enter a European market, but for some reason it seems most of them are not applying it to the Chinese market.

What would you advise overseas retailers looking to make the move into China?

My advice to overseas brands would be to take a step back and think about their product, find out if it is fitting for China or if they should instead develop something else that would be more in touch with the customer base. Then as a second step start working on their roadmap and only after that begin to think of potential channels to sell into, like Alibaba or JD.

They also need to think about budget and have realistic expectations. We see many brands thinking about entering the Chinese market with a thousand Euro per month, for example. This doesn’t work.

In order to be successful you need to have clear expectations and understand how your budget and your roadmap will fit those expectations. I always suggest to brands thinking about getting a foot in to go to China, understand the customer, do extensive market research and have concrete and realistic expectations of budget. Then once they have a clear roadmap, they need to look for the right partner and trust that partner to know the market better than them.

The Chinese market is full of potential, but it is still a very challenging one. Most Western companies need a partner in China, someone they can trust 100% as the market is so different to what they are used to.

We have a consultancy arm where we educate our partners about the customers and the market dynamics and have almost daily consulting sessions with them. There is a strong communication line in place between our operations team and their operations team overseas. It’s a two-way street. Our partner needs to understand us and the Chinese customs, but our team in China also needs to understand how a UK company, for, example works, as we do have very different ways of doing so.

Are there any examples of brands that you think have got it right or not?

A good example is a partner of ours who did everything right from the start. They were very dedicated to understanding the market; they were visiting our offices in China and having workshops there even before any contract was signed. They were showing a real interest in understanding the Chinese retail world. There was a strong level of trust in our partnership. They were also building a dedicated team in their home country to work exclusively on this project. By doing all this they were showing they were dedicated to making this work.

On the other side, a department store which was opening a lot of shops in the biggest cities of Shanghai had to close them a month or so later. This wasn’t one of our partners, but their mistake was that they were offering the same exact fashion as they did in their home country.

This didn’t work for the Chinese customer; it was too big to fit the women and it was viewed as “old” fashion by the high street of Shanghai. The Chinese millennials are always looking for ways to stand out from the older generation, so that offering did not work for them. It wasn’t adapted to their mindset.

A really interesting example is Aldi, the German discount supermarket, who is very successful in China. In Europe Aldi is a place where you can buy lots of things at a very cheap price. What they did in China was reposition themselves as a premium supermarket.

They completely changed the concept. Instead of building huge warehouses outside of the city, they began opening little stores in the middle of Shanghai. On top of that they started selling high-end international items at high prices.

They also did a lot of omnichannel, and as a result Chinese customers are ordering from them online much more than offline. They have completely changed their DNA in order to be successful in China. They have adjusted their communication, their SKU, their portfolio; even their positioning.

What are the key differences between Chinese companies and Western ones in your view?

Customer communication is the main difference in my view.

Chinese brands interact with their customers and engage with them very differently to how it is done in the Western world. If we look at online channels in China, there is a new one coming out every two or three months, whether it is ecommerce, sales, social media, marketing, etc. The ecosystem is constantly changing.

The Chinese domestic brands are very quick to adapt to these new channels compared to how it is done in Western countries where everything is much more rigid and static.

Taking the example of TikTok, it is currently overtaking WeChat as the highest amount of time spent per day by the Chinese customer. But very few brands are actually marketing on TikTok. A successful strategy would be to quickly adapt, be more flexible and experiment with these channels to build up followers and target them directly. This is something Chinese brands do.

What are the biggest shifts taking place in ecommerce in China in your opinion?

There is a very interesting channel that came out two years ago called Pinduoduo. It skyrocketed to become the second ecommerce channel in China after Alibaba, even surpassing JD.

It offers the possibility to do what is called group buying. When you find a product on this channel, it will have two prices: one would be €10 for example, and the other one would be €2. You can buy it at €2, you just need to find four other people in your network who would want to participate and buy the same product.

It’s a type of social commerce, and it’s all based on engaging your network. The merchants are not even spending much money on advertisement anymore, they are relying on their own customers to advertise their products and make the sale. This platform is very popular in tier three and tier four cities where people are buying everything through it, even everyday supplies like toilet paper. We don’t suggest it to our partner brands as it targets a different type of customer, but I find it truly fascinating.

Another trend I found very interesting is a sort of private group selling, used by Chinese sportswear brand Anta Sports. The company gives incentives to its own employees to have them build private groups and sell online through them. The groups are a maximum of 500 people, which can be relatives, friends, or even customers that were browsing earlier at the store.

Each employee gets an individualised QR code and sends it to his private group, offering them a rebate if they use it when buying a specific product on the company’s website. That employee gets a percentage of the sale if his QR code was used.

It is a way for companies to incentivise their employees and use them to sell online, as brand ambassadors. By making it personalised – having your friend send you the message – there is a much bigger engagement from people.

This is particularly useful with the current coronavirus situation, as employees are all home, so instead of doing nothing they are building groups and selling online on behalf of the company.

It’s quite new and I find it very interesting.

Do you see these approaches travelling from China to the West?

I believe there are four things delaying this development in the West.

Firstly, we don’t have what could be defined as a “super app”, something like WeChat. With WeChat you can do everything, you can shop, buy tickets, engage with your friends, etc. It is the link between the offline and the online world, it allows them to melt together. This is missing in the West; it needs a big company to make it happen.

Secondly, we don’t have the online payment facilities they have in China. Cash has become almost irrelevant for them as online payment is completely integrated. The West is not there yet, you have to manually enter your credit card number, sometimes leave the website to go on PayPal, etc. It breaks the chain and makes it complicated.

Thirdly, the West has a lot more regulations than China. To set-up something like the private groups where employees sell on behalf of the company would require a gigantic amount of legal paperwork.

And lastly, the mindset is very different. It’s not in the Western culture to promote something bought to friends, to try to get it at a cheaper price through group buying. But for Chinese people it is natural to share a good deal with their network as it’s a way of helping their friends. Many of them even view it as a responsibility.

I personally have the impression that the two worlds are going even wider, they are drifting further and further apart. It doesn’t mean that the West will not develop, it just means that it won’t necessarily be in the same direction.

Are there any small brands in China you feel are doing innovative things?

An example that comes to mind is Forest Cabin, a skincare brand, which managed to have a quick strategy turnaround when coronavirus happened. It was an unknown brand which was doing 75% of their sale offline. When the stores started to close because of the virus, they were almost bankrupt. They knew their only solution was to go online but they didn’t have the funds to advertise or hire influencers, so they trained their employees in livestreaming.

The CEO and founder also took part in a two hour live-streaming session on Valentine’s Day where he also thanked medical personnel and health employees and pledged to donate products to them. The video went viral, and Forest Cabin made 45% more sales that day than the year before. This is a good example of flexibility and quick turnaround from a brand.

Images courtesy of Azoya