How is digi.me pioneering a new approach to personal privacy?

Privacy is a big deal. As individuals, we’ve never been as aware of, or empowered, when it comes to our data, who has it and what they’re using it for. And businesses all over have felt the sting of not protecting that data properly or using it in ways people are uncomfortable with.

Despite all this, data is at the heart of the customer relationship. You have to know your customer in order to truly build rapport with them and that necessitates data. Digi.me wants to give everyone control over their personal data and enable them to share that with brands in exchange for a service or offer in a safe way.

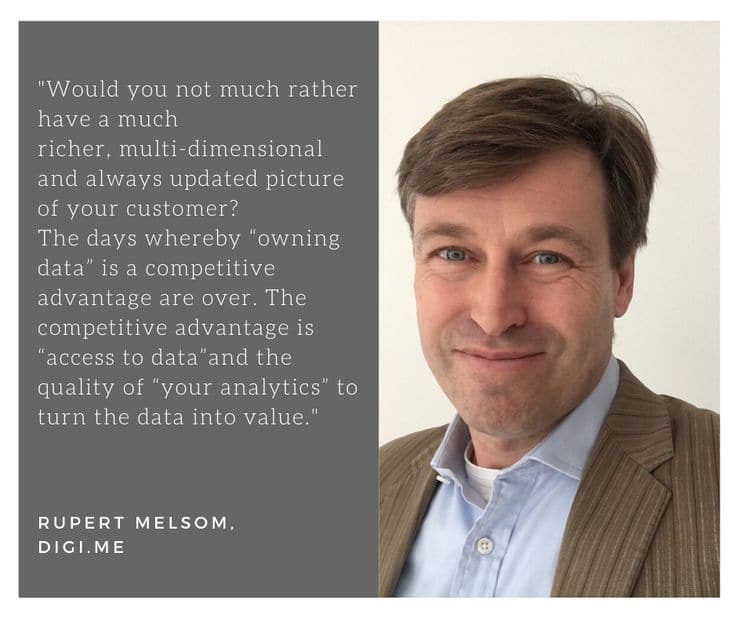

We spoke to Rupert Melsom, VP Business Development, to find out how digi.me works, the innovative way brands can leverage personal data and why the customer relationship is key.

Rupert Melsom, VP Business Development, Digi.me

Could you describe digi.me in a nutshell?

Digi.me is a global personal data ecosystem. This enables individuals to connect with organisations to share their data, or allow access to their data, in return for a service of value. We focus on two core things – data routing and consent services.

We are an interoperable data grid where people can choose whether they want to control and share or take their data with them to use elsewhere. The user has complete control over what data is shared with which organisations and if they want to stop sharing it.

What might someone use their account for?

Digi.me is relatively new for the consumer retail market. The number of value exchanges possible are limitless and retailers can create their own, as long as they ask the consumer to share access to their data for the value exchange(s) proposed. We see uptake being driven more by convenience and usability for the consumer than it being because the consumer really wants to own and control their own data.

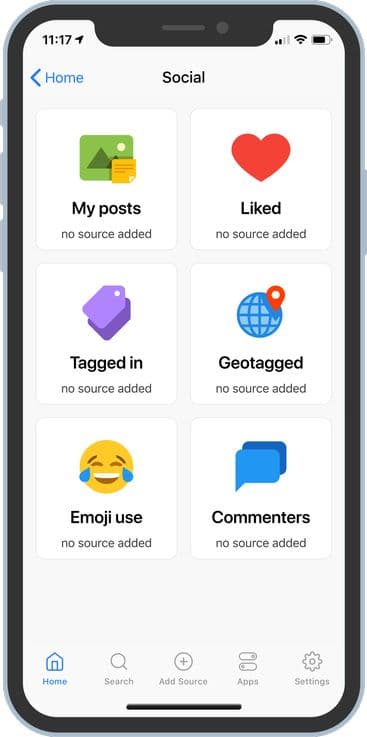

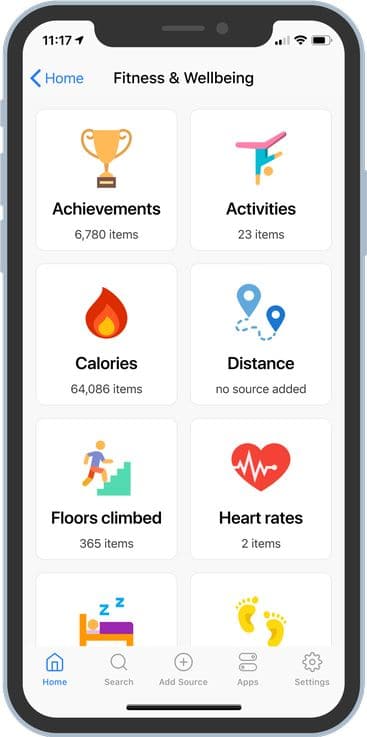

The first level is that you can have a backup of your digital footprint from bank accounts to social media accounts to wearables and even your medical records. As an individual, you own, control and store all your own data in your own dashboard. You can monitor all your data and search within that for specific information such as bank transactions. The data is stored in the location of your choice for example in an encrypted container within your own Microsoft OneDrive, Google Drive or Dropbox account.

The next level is that you as an individual can decide to share access to your digital footprint with any third party of your choice. You can choose to exchange some of your data or make it available for something of value to you ie a quote or an offer.

There are all sorts of different privacy protecting applications such as analysing your social media to make sure that your accounts don’t let you down when going for a new job. For example, the application would look at all your social media posts and recommend adjustments to posts to change language etc.

There are apps to analyse your spending across all your accounts without having to give the data to a third party. Another application will let you upload all your medical records so that if something happens while you’re out of the country you can share private access to those with a doctor for treatment.

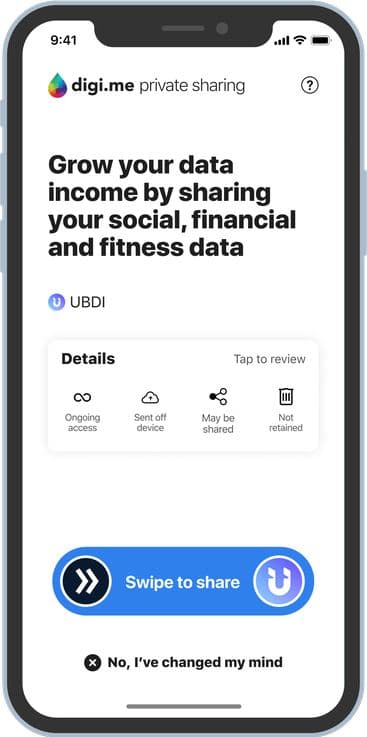

Other examples might be a loan application in a single button click you can upload your details and get your offer. Or you can participate passively in UBDI.com panel research by allowing auto-analysis your data, earning you income whilst you remain anonymous.

All of that is freely available because digi.me believes that you owning your data is your human right. It doesn’t cost anything to the consumer to retrieve and obtain their data. The sharing of the data is in essence free to the consumer too. This is where the digi.me business model comes in.

Digi.me only charges organisations a processing fee when the consumer has agreed to share access to their data in return for a service. The organisation is charged a flat fee of 10 cents for each transfer, irrespective of how much data the two parties agree to exchange.

We never know who our users are because they are entirely anonymous, and we don’t hold any data on an individual. We are only the grid operator. We don’t really know what they are sharing with a particular organisation but we can say we facilitated this connection between the individual and the organisation, so we charge the fee for that. Think of us as the digital postman, whereby we can deliver the item but not look into the envelope.

We never charge more $3 per year, per service provider, per client. For example, if my bank was to always provide me with the same loyalty, fraud or financial service and they update their records an unlimited number of times a day, they would never be charged more than $3 a year.

How much control do users have over the data shared?

The golden rule is that the individual is always in control. If you do not want to share data, or if you want to stop sharing, or if you want to pull back any past data sharing and ask the company to delete your info, you’re the one who’s in control and you can initiate that.

In the case of retail, an individual may be presented with a certain offer or service in a mobile app or on the retailers’ website. In order to access the offer, the retailer will ask the (possibly anonymous) person to share some information. With digi.me you consent to this so that the transfer is facilitated. It is a standardised contract that is very easy for the individual to review and keep track on what one-off, or recurring, data shares they are giving access to in return for which services.

There are two ways that the data can be shared: one is very similar to today’s common practice – whereby the individual transfers their data to the retailer’s domain for analysis by the retailer. Subsequently the offers are matched to a profile and a promotion is made to the user. Moving the user’s data to the analytics held by the organisation is what digi.me calls “Data Sharing”.

The other way is where the retailer never actually receives the data but takes their analytics to the user’s data locally in the app, or on a user visited webpage. The generated analysis could be that your shoe size is 41 (European), your favourite sport is running and the most followed brand on your social media is Brand X.

The organisation may then consider making you offers for Brand X running shoes, matching your size. This could be carefully targeted when you also allow your wearable data to be analysed, so they know how old your current running shoes are. This is what digi.me calls “Private Sharing”.

The beauty of this targeted, highly personalised, service is that it remains entirely private despite there being a direct communication possible between retailer and (anonymous) user. The data also remains in the user’s private domain meaning the individual is much more open to provide access to a much more in-depth data set of their life.

How are brands using the system at the moment?

Last year we saw that service providers and companies started realising that the best possible way for them to engage with their customers is by going back to basics and respecting the relationship between the customer and the organisation.

As part of that relationship, you explain what kind of information you require in order to provide the best possible service for that customer. It is surprising how many clients and consumers at this moment in time do not want to share data with their service providers.

They try to avoid cookies. They try to not sign into their accounts. They try and avoid being tracked for the simple reason that they feel uncomfortable about what is happening with that data.

Research says that people are actually very willing to share data, much more so than what you would actually anticipate, but conditional on knowing why and what for. They want to remain in control and know that their data is being treated with respect. As a result, it is foreseeable that there will be a migration towards a smaller number of very trusted brands that users engage with.

One example is a use case we did with cxLoyalty and the lingerie brand Hunkemöller. They have a hyper-personalised proposition that built up engagement with the consumer and made sure that the loyalty of the consumer was therefore much higher. By doing so they could transition their loyalty programme from one often used for discount vouchers to one far more focused on client engagement and relationship building. By taking the user on a journey and learning about their interests and drivers, a more suitable value proposition could be made, which also results in valued cross-sells. The access to granularity of data, whilst upholding privacy, meant a win-win for all.

The second use case was with MasterCard and Pathé cinema group’s operations in the Netherlands.

In this case, the visitor consented to share granular data with the merchant in order to provide a curated experience. Not only would a cinema ticket for a premiere be offered, but a range of other services, such as food and beverage at the cinema, taxi service to and from the cinema, or the person’s favourite takeaway to arrive timed to their arrival back home to coincide with an offer for the film associated boxset via their home streaming service.

All of those things were wrapped together in an experience that was personalised specifically for that individual. Merchants are starting to realise that because they have a trusted relationship and explicit and informed consent for offering certain types of services, they can provide a much better, tailored valued experience, even when that involves internal services bundled with external services.

The relationship improves, loyalty improves, the service offered is deemed more suitable and convenient, and the cost of obtaining the data actually reduces. They brand is getting more return on investment just by paying notice to privacy and respect of personal data and the relationship with the customer.

How do your ideation workshops work?

There are multiple ways that organisations can adopt and experiment with digi.me.

We have a developer website, which is aimed at tech builders and developers to start building or enrich existing retailer apps and webservices. With the provided Software Development Kits, you can effectively build anything yourself straight away. Any parties who wish to have direct support in order to guide them through the development phase quickly, can reach out to our hands-on support team via a dedicated Slack channel.

We also run workshops with companies wanting to explore this and help co-develop products. There are lots of large organisations that go down that route because it’s a lot faster and more efficient for them.

We would typically start a workshop with the question – how would you serve a single customer best if you had unlimited access to the most granular data?

Then taking a stepped approach seems to resonate with most clients. Easy quick wins can actually be very powerful and rewarding. Equally, we set out the strategic aims of eg. a hyper-personalised, privacy centric client engaging loyalty and sales.

We go through various different use cases in the workshops and explain the pros and cons. The next step is building a proof of concept and making sure that it is all provided in a way that the organisation would feel comfortable with deploying into the market.

What are the most innovative ideas that you’ve seen for how brands might use the data that they access through your system?

When we look at the ecommerce sector more widely than just retail, there are some very interesting value propositions.

For example, airlines that are subject to EU rules are obliged to compensate requesting travellers when a flight is delayed for a certain amount of time. For travellers the delay is unfortunate as it is, but it can become a negative brand experience, especially if they don’t get any information and have to fill in a lot of paperwork to obtain compensation.

The airlines have an opportunity to create a smart delay proposition that gives the traveller certain services as and when they have incurred a delay. Think of updates, food and beverage vouchers, lounge access and automatic compensation settlement.

Often these products do not receive sufficient practical traction as the individual has to remember to keep updating their scheduled flights. With digi.me, the individual would have agreed to share certain data such as flight info and geolocation from their personal data store, so the airline knows (for this purpose only) when they’re in the airport. It would then be able to recognise if their flight is delayed from the global flight status data feeds and automatically send the customer services for any levels of inconvenience.

This use case could also translate into retail. You might always buy your coffee from the same chain and in the loyalty app you may have given them (privacy shielding) analysis only access to data like your messages. The company’s algorithm privately scans your messages on your device only for the trigger event phrase ‘let’s go for coffee’. The coffee company never sees any of your data, but their service picks up the trigger event. Together with a check of your geolocation, it sends you a notification that your favourite coffee is ready at your nearest coffee shop.

Most consumers and retailers are not yet ready for that level of convenience. The education on truly being the owner of your own data is something that is becoming increasingly adopted by the mainstream. Once that is deemed “normal” and trusted, you can imagine demand for personalised and highly convenient propositions like this.

Ecommerce providers who do not already explore how to operate in the Personal Data Economy may find that playing catch-up will be doubly difficult. They would be on the back-foot service offering wise, have less granular data to base their analytics on – due to being late to be trusted with the consumer’s data – and last but not least, they would have lost out on the “grace period” in which the early adopters could liaise with consumers in an open and transparent way by asking to help refine their personalisation algorithms.

Is there an opportunity for the customer to gather data from a visit to a store and add that to their profile to use elsewhere?

Yes, because the individual has the rights to all of their own data. If we look at regulation in Europe for example, under the GDPR, the individual can ask for all of their data back under their data portability rights.

It’s a lot easier if you can click on a synchronisation button on a retailer’s website, so your data is continuously updated in your own digi.me profile while you’re interacting with that retailer. You can then use that with the same retailer, but you can also use it with other retailers. Effectively it is the reversal of cookies.

The user does not have to opt-out of cookie tracking by the service provider but has the option to log their data by having their own cookie streaming their web browser behavior to their own digi.me. If they then want to share that data, they opt-in (by means of issuing consent) to share.

At that point, most retailers will turn around and say, ‘hold on, I’m giving my data away to the consumer who might give it to the competition’. That’s true but on the other hand, as a retailer you only have one small snippet of the overall transaction data of that individual. Would you not much rather have a much richer, multidimensional and always updated picture of your customer?

The days whereby “owning data” is a competitive advantage are over. The competitive advantage is “access to data” and the quality of “your analytics” to turn the data into value.

For example, if I’ve just bought a pair of Nike shoes, I might then be targeted by an email trying to sell me another pair. It doesn’t really make sense. For the retailer to improve that offering, they might want to give back the data that they hold on that user, which is a stepping-stone for them to ask the individual for access to their whole data profile.

Now they can make a valued offer by knowing whether I most likely bought those shoes for myself, for certain types of sport or leisure, and what my favourite colour or interests are. Such information might constitute the offering of a certain type of T-shirt, which has a much higher conversion rate than an additional pair of shoes.

Do you think we may see fewer discounts if we have true personalisation?

I think it depends on the sector and the positioning of the retailer. If you make the right approach with the right service and the right proposition, why should you have a discounted proposition?

In actual fact, if you get the timing right and the proposition right, you might even have the opportunity to increase the price because it’s a massive convenience for the individual. You could actually get more margin because you are the loyal, trusted service provider opposed to trying to always compete only on price. The balancing act is to offer fair pricing for the goods, the service, the loyalty and convenience.

Do you think retail will carry on gathering anonymous data in shops?

It all boils down to what is your relationship with the individual client and how can you have the best possible offering as a retailer?

You might want to continue to collect anonymous data and most parties will. It might be helpful on the side in the same way as today retailers are buying big data and putting generated profiles against the personal data that they have on their clients.

What you might want to do is consider how does that feel for the consumer? The consumer is becoming more and more aware that a lot of data, which is supposedly anonymous, is being collected when they walk in and out of shopping malls and (auto-)connect to the Wi-Fi. They know that nothing is for free and they know that a lot of their data is actually being stored. But they are not really happy about it. When alternative solutions become widely available, we believe people will vote with their feet – particularly when it comes to the way they have been treated based on fundamental values such as brands’ issued trust and respect.

What you might want to do as a retailer is be open about it and say, ‘we might collect some data’ or you take the moral high ground and say ‘no we actually don’t want to collect anonymous data because we would much rather have a fair and honest and respectful relationship with you – one that is privacy protecting for you’.

By doing that as the early adopter, you have the benefit of positioning your brand in a privacy centric way and capturing the respect and buy-in from the consumer. As a brand, you have the opportunity to put your brand name to privacy and use the personal data ecosystem that is available.

You might give up a little bit of your own transaction data, which, to be honest, is not really losing much when you compare how much more data you could get directly back from that individual. It’s all from one person, fully consented and multidimensional. It all boils down to the question – why not just ask your customer?

Do you envisage your system ever working with advertising?

I think that there is scope for that, but I also think that there is a bigger picture.

There will always be a market for generic advertising because people will want to know what non-personalised range of services and information are available in the world. They don’t only want to receive their increasingly tailored / convenient / tunnel vision-based services because they might refine and determine who they are. If they determine who they are too much, the individual may become what they are being portrayed as which is very dangerous.

The beauty of where we’re moving to is that you get that personalisation, but also enable the user to switch the personalisation off. You should be able to dial up and dial down the level of personalisation that you would like. This level of user control is what we’re aiming for strategically within digi.me.

At the end of the day, everyone has the right to privacy. Everyone has the right to their own messages and has the right to determine what level of tailored content they would like to receive and what level of content they might actually want to just switch off altogether.

I think that the beauty will be in the parties who understand the nuances of the customer’s life most of all. Understand that somebody might’ve got out of bed on the wrong side in the morning one day and is therefore not really interested in receiving a whole set of tailored messages. Maybe without that single factor, the offers would have all been perfectly appropriate. In which case, maybe they are most suitable tomorrow.

The game is not collecting as much data as you can. The game is how to make sure that your analytics are better than those of your competitors. The only way of improving your analytics is by getting in there early and working your analytics models hard to ensure they are refined enough to be more valuable than annoying. There will be a grace period in the eyes of the consumer for anyone genuinely trying to co-create valuable personalised services.

Parties who start now still have that leeway. Waiting for two or five years is too long. All of these services will be more refined, very convenient, well positioned and have wide adoption because they’ve come from a couple of the big techs that already have that clever insight and knowledge to understand and analyse the customer.

Anyone hesitating on exploring the Personal Data Economy will probably miss the boat and incur increased competition – not just on price, but also on core values such as respect and “truly” knowing or understanding the customer.

Companies that wait will be the ones that will forfeit their positioning for some of the very big conglomerates that can easily transition from one sector into another. You might want to consider leapfrogging them and gaining access to a wider multidimensional private data set and having a really good trustworthy private relationship with your end consumer.

Brands have that relationship with the end consumer at the moment. That’s the one ticket they can really ride on in a way that shows true consumer understanding.

Images courtesy of digi.me

Get in touch if you’d like to book an ideation workshop.

You can also read more about the Me2B model of individuals sharing their data in exchange for better services and offers via this whitepaper.