Shift to sharing – Shing on bringing the access economy to retail

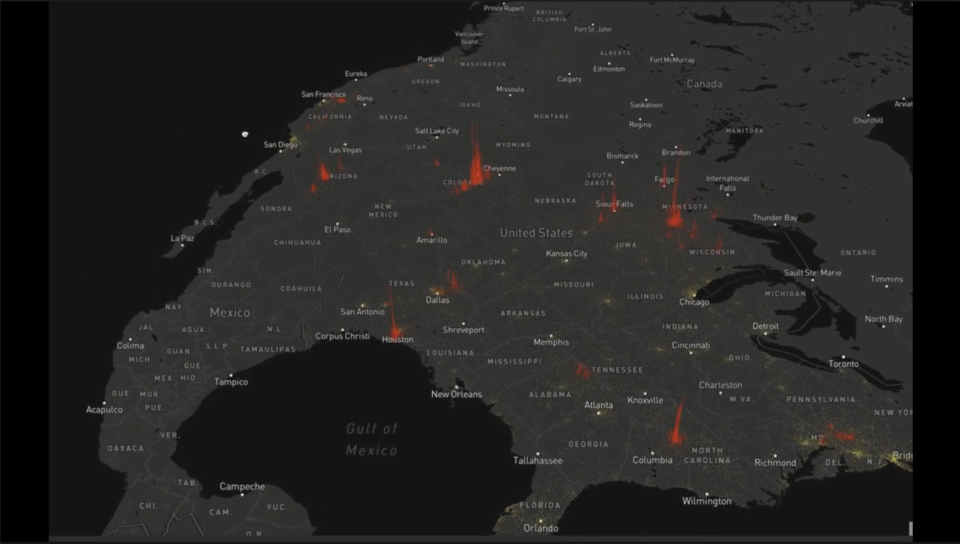

The access economy has reached mass consciousness with the rise of recognisable brands like Airbnb, Spotify and Uber. Many of us in our day-to-day lives are increasingly happy to pay to access certain things, rather than own them.

Shing is a new platform helping retailers and brands enter the sharing business. It enables them to offer access to their products via rental, lending or sharing, instead of just outright sales. This opens up a whole new world of opportunity.

We spoke to founder and CEO Alexander van Riesen about how a shift to rental would impact retail profitability, opening up a new revenue stream for brands and bringing sharing to the masses.

Could you tell me what Shing is in a nutshell?

Shing is a software-to-service platform catering to the needs of consumer brands, manufacturers, or product companies that want to start renting out their products or giving access to their products instead of selling them to customers. We’re building a white label platform for enabling a move from ownership to the access economy.

We’re also looking at the logistics and handling of the products as well. Some product manufacturers want to manufacture the product, but don’t want the hassle of renting it out and doing the maintenance etc.

We then look at the business model of that. You have the business of cost of goods sold. We’ve started to talk about COGR – the cost of goods rented. Do we buy the product from you, or are you as the product manufacturer still going to own it and we do a profit share?

It’s about spinning around that model. We might not be able to sell 1,000 jeans because of the limitations of the rental economy. But if we manufactured 500 items, we could now earn $40 on the cycle of the product, instead of just $10 per outright sale. We make less volume, but we still make a decent amount of revenue.

If you go to Stockholm, London, Milan, Dubai, Sydney, New York, Los Angeles, you’ll find the same brands in the shopping centres. If you like the style of a certain brand, why can’t you visit London and have an outfit waiting in the hotel. Why do you need to haul it on the plane?

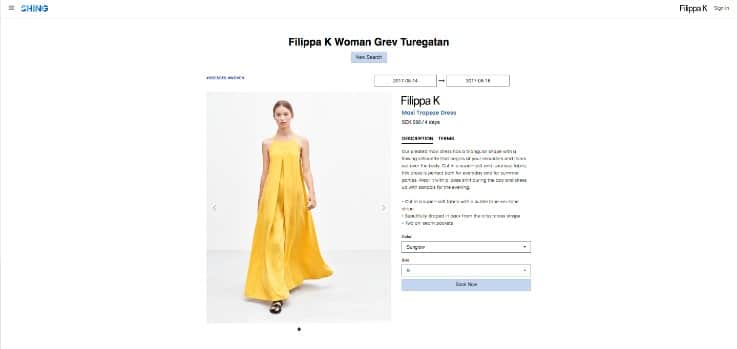

Can you subscribe to dresses from a brand for £100 a year or £100 a month, so you can just got to the store, take out two dresses, wear them for three days and take them back?

I think there comes a point where you want to own things because the frequency with which you’re using the item is so high that it makes sense to have anytime access to it. Whenever that point drops to below a certain threshold, then you’re going to say, “Wait a minute! I’d rather rent this.” Then you come into costing the lifetime value of the customer.

Can you tell me a bit more about the pilot brand stores with Houdini and Filippa K?

We came to them because we are looking at consumer product brands that are early adopters in access economy.

Filippa K is a company that is very environmentally conscious and sustainability is very high up on their agenda. They have an initiative called Filippa K Lease in selected stores where you can go and you can rent their clothes. However, it’s a manual process, so they don’t have any IT support for it. Our platform where we are developing software-to-service for this was a fit for their model.

Their incentive comes from a consumer perspective. “Some clothes I might not need to own; I want them for an occasion tomorrow. Maybe I want a nice costume or dress for a midsummer party, but I don’t want to own it.” They see this as a complementary business to an outright sale.

It’s the same with Houdini. They’re also a very small company compared to the big players like Zara, H&M and North Face. The founders of Houdini are again very environmentally and sustainability aware, so they also have a rental initiative in place, but it was handled manually.

They do it for the same reason because they do outdoor clothes and active wear. If you want to go hiking, climbing, skiing, you have shell clothes and then you have the fleece clothing. If you need an outer shell, you can rent that for four days and then return it to the store.

Can you tell me what percentage of those businesses are rentals versus sales at the moment?

Their main business today is outright sales. Again, it also comes into pricing models, what is the business model around this, and how should you price the products versus an outright sale. But it’s a fraction of their annual turnover. It is significant though in that they’re not doing this for fun. They’re doing this to learn and to understand and to be able to iterate.

If we fast forward to 2025, do you have any predictions about what percentage of their products will be rented versus sold?

I think it’s going to probably become a bit more complicated. Eg is Houdini going to rent out all their clothes or are they going to sell to aggregates like Rent the Runway that buy stock to rent out? If we’re going to a ski resort, will I rent from Houdini or will I rent from the ski resort, or will I rent from the hotel? I think there will be a hybrid mix in the ecosystem.

People overestimate the change that will happen in two years and underestimate it in 10 to 16. Everything you did back in 1995 with the internet was correct, but it took 20+ years for it to take off.

By 2025 and beyond, we will have started seeing a different mind-shift in ownership – do I need to own it? But it’s really, really deep in our DNA because it’s been for the last couple of generations that we own things. Right now it isn’t on the radar, but by 2025 to 2030, I would say that most quality product brands will have an access initiative going on.

How easy do you think it is for major brands to shift into the sharing model? Or you think the brands that are really going to embrace this are going to be the start-ups?

In the market today, you have Rent the Runway, for instance. They are like a warehouse or a shopping store. They’re like Harrods, for instance, right? Harrods buy products and then they resell it. What Rent the Runway does is they buy dresses from all the brands and then they do the service. The brands don’t do it themselves, and it’s still an outright sale from the brand to Rent the Runway and then they’re renting it out.

I think brands that are innovative will launch an access model. The challenge a brand will have is that their current business model, their current incentive system, their current distribution chain is for an outright sale.

I think the companies who would be winning in this are saying, “This is a triumph for us. We do it as a complementary service.” They’re probably going to do it in partnership with someone or as a freestanding subsidiary outside of their current operations.

Then of course there are the new product companies that don’t have any legacy. There’s a Taiwanese scooter manufacturer called Gogoro. They have 200 electric scooters in Berlin which are free to use with an app and you pay as you go and you can drop it within the city centre.

Again, they’re not sitting in a distribution chain where they have a distributor, a reseller, and consumer. They could start fresh and saying, “Rather than selling it through a value chain where everybody wants their margin, we finance this, we put it out, we work with a service partner to maintain the motorbikes.”

Do you think the profitability would be different in a company that switched just to a sharing model?

The gut feeling is that if you’re looking at cars, one car sharing car is replacing 10 other cars. Let’s say you want to hike the Wicklow Mountain. You need a tent. You need a backpack. You need sleeping bags. You need hiking boots. You need shell clothing, and an outdoor kitchen, and everything. Let’s say you invest €3,000 or €4,000 in equipment – it’s an outright sale. We come home and we put it in our storage because next week we do something else.

If we would have rented this, then the next person who’s doing it the week after can use that equipment instead, but in doing that, it’s just one item being manufactured instead of two. Unfortunately, then it’s going to take a hit in volume, and if volume takes a hit, then usually profit takes a hit. You quickly open a pretty big Pandora’s box in saying, “Okay, if we don’t consume anymore, what do we do then?”

We have a joke about how most of our clothes just hang around a lot. They hang in the store, and then I buy them, and then they hang in my wardrobe, and then I take them to the dry cleaners and they hang there for a while, and then I take them back, and they hang in my wardrobe, and then I wear them. The actual wear on some clothes is high, so I’m getting the mileage out of it, but a lot of other things I use so seldom that I think why do I need to actually own it?

I think my gut feeling is that volume will go down. You will still be able to make money, but it will maybe not be an infinite growth all the time. Outright sales are going to be around for 10 more years at least, so companies will survive, but in the long run I think things will change. I compare it to the music industry. I think you will still be able to make money as a musician, but you may not be able to make as infinite amount of money as before.

Why are some access companies like Uber and Airbnb taking off and others aren’t?

I think the general trend is that brands that we take for given today might not be around in 15 years’ time and that’s due to the fact that the average lifespan of the company has declined over the last 65 years. A company’s average lifespan has gone down from 80 years to 15 years.

No matter how successful you are today, you might be out of business tomorrow because it changes so fast, and it’s so dynamic. It’s down to customer interface, execution, and trends. It’s about that experience that is really, really user-friendly.

Then sometimes you just have two competing different technologies, and then one takes off due to the fact that the distribution is better or it’s got more viral spread. Windows probably wasn’t the best operating system back in 1980s, but Bill Gates made a brilliant deal in saying every IBM computer was shipped with Windows on it.

Airbnb, for instance, hacked Craigslist in the beginning. Because there was no market liquidity on Airbnb, they used a capability where whenever you put an ad on Airbnb you automatically post it on Craigslist. All of a sudden, it’s got the momentum and then they executed better, and then you get critical mass.

Today we see a dominant trend: either you have peer-to-peer lending, or you have a third-party service. Let’s say I borrow something from you. First of all, do you want to see yourself as a rental company? Is that your main business? Is that what you want to do? Secondly, there are some challenges renting from your neighbour if something happens. It creates a certain sense of, “I own it. It was mine, and now it’s ruined or damaged.” But if it’s owned by a third-party, then I think emotionally you get less attached as well.

What are the major factors that you think are going to tip sharing into the mainstream?

It’s a behavioural shift. I think for younger generations it will go faster. I usually say, “If you go to a hotel and you sleep in the sheets, you didn’t bring your own sheets, did you?”

People are like, “No! I did not.” Then you see the shift in their faces and they go like, “Yeah, you’re right.” The trust here is that it’s clean and it’s germ-free.

If you were at an auction and there was a dress that had been worn by Marilyn Monroe, it will fetch a price far more than the fabric it’s made of due to the history of the item. Let’s say we could start tracing the history of items. What if the tent you are sleeping in on Wicklow has also been on Mt. Everest with this expedition? All of a sudden, it becomes a little bit cooler – not just this tent series, but this tent.

It’s slowly sifting into society. Year-on-year, you will start seeing more and more acceptance from people. I think we will have the same pattern as with e-commerce. It might go faster and the reason is that technology will change faster. There has been a bigger change from 1995 to 2015 than from 1975 to 1995. As we know that doesn’t stop.

How can you apply tech to this?

One thing is around delivery. It’s the cost of last mile delivery. When you look at how payments are getting more and more integrated into the smartphone; it’s getting more and more accepted. You’re becoming used to all these services where you access things more than owning them.

The Internet of Things will also play a part. If we’re talking about hardware that is connected with a battery or electricity supply, it will be able to communicate with the rest of the world. One of the power tool manufacturers that we talked to, are looking into a model where they still own the power tool and while it’s not being used it doesn’t cost anything. But as soon you pick it up to drill 3 holes, then they start charging for it.

If you look four steps ahead, to a time when we have true autonomous car driving, then you can have delivery pods. That means you can order equipment, such as a camera with lenses for delivery in 30 minutes. You open the car with your code, which identifies you as the rental person. You use the equipment, return it to the pod and off it goes. I think again we could be seeing this in 10 to 15 years.

Images courtesy of Shing

Find out how others are disrupting retail with our look at 10 brands bringing that to life.

Want to quickly and easily connect with the players kick-starting trends and inventing the future of retail? Find out how you can transform your team’s thinking using Insider Trends’ little black book here.