VERSA on what voice experiences and the age of ask means for retail

Are you listening carefully? We hope so because if you’ve had your head in the sand over voice VERSA is going to shake you up. This Australia-based company creates bespoke enterprise-level voice experiences that utilise the huge explosion of voice-enabled technology such as Amazon’s globally recognised Alexa.

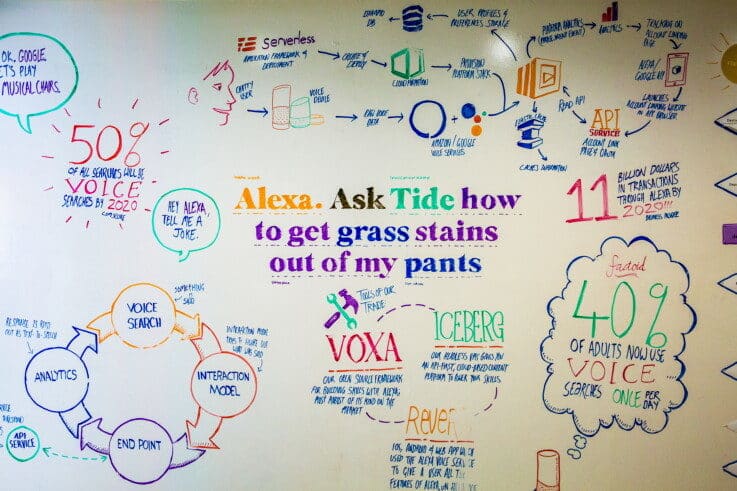

Launched in 2017, VERSA is the result of a partnership between two leading agencies. Although young, the company isn’t waiting around and has already completed voice experience projects with a number of large brands. It believes the opportunities are plentiful for providing better customer experiences and even new commerce channels via voice. It seems there is no time like the present to get your own house in order when it comes to voice as VERSA reports that in less than two years 50% of searches online will be done via voice.

Guy Munro, VERSA’s global business director tells us everything you need to know about creating effective voice experiences, the use cases, how voice can be used for commerce and why everyone should be thinking about voice.

Can you describe VERSA and what you do in a nutshell?

VERSA is an Australian voice experience agency created in partnership by Rain, the US’ lead conversational specialist agency, and Deepend, Australia’s largest independent digital experience and design agency. We literally create the equivalent of apps but utilising voice as the mechanism. Generally, Amazon Alexa or Google assistant are the main technology providers for those voice experiences.

What exactly is a voice experience?

Voice experiences are definitely new in the grand scheme of things. Apps have been with us for the better part of 10 plus years since the iPhone came out in 2007. From a commercial perspective, with voice experiences you’re talking about a medium or a technology delivery mechanism that’s only three and a bit years old. In Australia we’ve only lived with it for nine months overall and then Amazon is even less as we’ve really only had that here this year. It wasn’t available to the Australian consumer at Christmas last year. From our perspective consumers are still getting used to voice in terms of what it can do.

The other thing that we’ve also found is that historically a lot of people haven’t probably had a great experience with voice. If you take the early days of in-car navigation which might be voice activated or even Siri for example, those earlier platforms haven’t been the best experiences for consumers. Siri promised the world and delivered not much. It was quite surprising because Apple pride themselves on delivering amazing experiences. Siri doesn’t come up in any of our conversations at a commercial level with clients at this point in time either.

These past poor experiences are mainly because of the natural language processing and what it’s doing now in terms of accuracy and the ability to understand what we’re trying to say. Computers and technology needed to catch up and it is now at a point where it’s far more useful for consumers to actually utilise the platform and elicit the right results to make it a good experience. And it’s only going to get better. The more people that use it then theoretically it should actually be a better experience for consumers from a day-to-day perspective.

One thing about Amazon and Google is we’re talking about introducing a platform that’s quite foreign to people. It’s actually not because as humans we talk all the time. There’s a bit of resurgence as to what the old days of communication were but obviously with a modern twist with things like dynamic content and of course being web-enabled. Yes, we’re speaking to a computer but it’s a humanised computer at the same time which is quite lovely.

What is your process with clients?

First off, we work with clients or prospects on what is the use case. This might start with a workshop to understand what the level of readiness is from the client’s perspective. Voice is so new in many respects it has been quite abstract and ethereal for a lot of organisations to understand and identify what the net effect would be from a benefit point of view. The first thing we do is we talk to an organisation around how voice may have a role to play within their business and then off the back of that the concept of readiness takes a slightly different form. We try to ascertain what information, content or what system they may have within their business that will support voice.

For example, traditionally if we’ve got a use case where we need to tap into live data, and that’s pretty common with apps and websites, we typically have what’s called an API. This lets us set up a dynamic content experience. We don’t necessarily have to have an API though, but the tradeoff is some kind of manual intervention.

For example, we’re working with the City of Melbourne at the moment. Every week they send an email to 70,000 subscribers about what’s happening in Melbourne for that weekend or that week. The way that email is constructed at this point in time is quite manual. The information is curated at a group level, but it’s still manually curated.

We held a workshop where we posed the question around ownership and who was going to maintain it. Who’s going to drive that manual intervention? Does that form part of the existing body of work? In the case of the City of Melbourne they were already gathering that information and to put it into the context of voice is really just summarising what that looks like for a voice experience. We were able to deploy a headless content management system that means they’re empowered to run that voice experience on their own end. This meant the level of investment from the client side was quite minimal and the body of work from a VERSA point of view was also quite minimal.

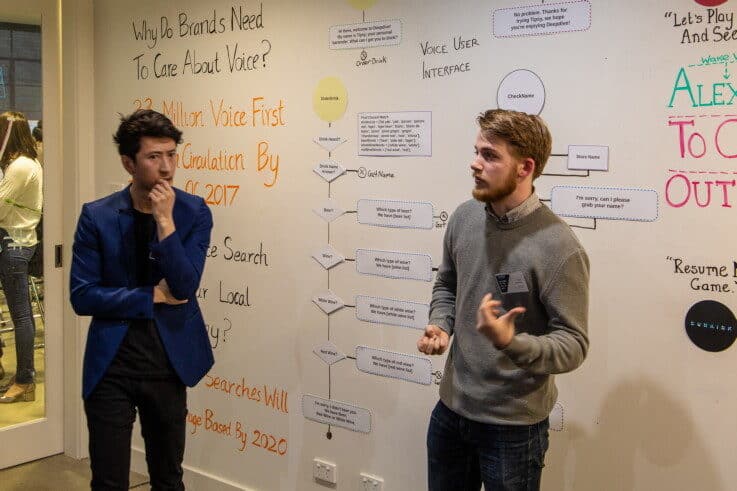

Once we have the use case, we then develop what’s called blueprinting and VX (voice experience). It’s like UX for websites and apps but in this case we’re defining what the voice experience should be. This is called conversational design.

We worked on a project with Flight Centre to create an experience that let customers use voice to find the cheapest flights. You can build quite a complex line of questioning, for example ‘Hey Alexa ask Flight Centre what’s the cheapest flight from Sydney to Los Angeles flying today on Qantas in business class after 3 p.m, so we identified off the back of that we needed a customised API. Flight Centre did not have a cheapest flights API, they had an API that would support all their flights but not the cheapest ones.

We then had to define the utterances or all the different ways you can construct the question. In a simple line exercise, as an agency very early on we posed a question to our staff around if you were to pass someone in the hallway and it was the morning how would you greet them? It’s quite subjective in terms of how you do that and obviously it’s very humanised. We ended up with about 48 different ways of saying hello – and we’re talking about one word, one instance, and one time of day for the greeting. If you think about that and the line of questions and the multiple variables that exist in those questions for something like flights there’s quite a lot of work in how you build the conversational flow. In the case of Flight Centre, we ended up with 40,000 different ways you can answer the question.

After we complete conversational design, we go into a traditional state of development where our coders and developers work with the technology to create that experience on the platform. We work either directly on the software developers kit that suits either Alexa or Google Assistant, or on a proprietary framework that we’ve created with our partners Rain which is called Voxa3. It’s quite a point of difference at this point in time for us to be able to build a voice experience on one platform and effectively flip it to another.

It’s a little bit like the early days of app development if you think about iOS as opposed to Android. Traditionally when you design for one there’s quite a bit of effort that’s required to flip it into the other platform and annoyingly that’s still the case now. But part of the competitive advantage that we’ve got is that we’ve created this particular framework Voxa3 and that enables us to work in different environments and be able to flip work relatively quickly. The net effect of that is the efficiency and the cost efficiencies of that which then trade off to the client at the same time.

After development comes certification and it’s definitely not for the faint-hearted, especially with an organisation like Amazon as their standards are exceptionally high. We work with Amazon locally in Australia. They also have teams internationally so once it gets rubber-stamped here in Australia it then goes to other teams that have never seen or heard or experienced the voice experience and they try and break it.

We’ve had very good experiences with that because of our roots are pure digital and we do a lot of work with government organisations, so we have the ability to get high quality work out the door. That’s helped in terms of the level of quality assurance that we have been working to. Once it goes out from certification typically it goes into a live status so that skill or the voice experience is out there in the market on the platform and people are using it. At that point we embed analytics into the voice experience to understand how people are using it, so we can identify where particular drop-off points might be or ways to enhance the experience. There are continuous improvement ways that we can make that voice experience better.

Are there any other top projects that you’ve been working on?

We’ve been fortunate enough to work with Domino’s Pizza based out of Australia. Their voice experience does two things. One is that you can set your ‘usual’ order, for example a margarita, garlic bread and a soft drink, and then ask Domino’s to order your usual by voice. Once you’ve placed your order it identifies your account in the background. The payment is taken by Domino’s from your credit card details on file. In this case that’s not an Alexa or Amazon transaction, they’re just providing a conduit to the sale. Rather than using the app, for example, Alexa is effectively the gateway for that transaction to occur.

Once you’ve ordered your usual, the second thing that the experience does is it to track the pizza. It taps into another API so you can be told when your pizza is being made, when it’s in the oven, when it’s on its way or when it’s at the front door. That’s all it does.

We were very deliberate on not being able to construct a pizza via the experience as that is quite complex. If you think of the visual stimulus that’s required when you actually order a pizza, and something like Domino’s where there are multiple ingredients and options it probably wouldn’t be a great experience to order a pizza via voice for now. We were very particular on creating, in some respects, a simplistic experience for the audience to be able to order their regular and get them used to using the platform. What we’re finding from an insights point of view is we’re seeing quite a bit of repeat patronage that’s coming from people who are using Alexa to order pizzas.

The whole idea was to reduce a bit of friction – they call it the wet chicken hands. If you’re busy in the kitchen and you’ve literally got wet chicken on your hands what can you do? Voice is a no brainer. Also, the fact that with voice, to a certain extent, you don’t need a user manual because the natural language processing is so good now. It’s not like you need to read instructions for an app or whatever. The idea is that it should be as conversational as what you and I can do on a day-to-day level. It’s getting there and it’s only going to get better. The thing that’s really exciting about voice is that it’s constantly in a state of improvement based on people who are using it.

What have you learnt about creating an effective voice experience?

If you think about your smartphone your home screen is probably almost identical to mine in terms of what apps are on there. For example, I’ve got my mail, I’ve got LinkedIn, I’ve got a calendar, I’ve got Spotify, I’ve got YouTube. I’ve got apps that I use very regularly. What we say to clients is the way to make a skill or voice experience useful is to anchor it into utility. If you think around the apps that have effectively earned the right to live on your home screen for the most part they’re going to be anchored in utility. That means they’re things that you use often and are also habit forming as well.

Most of the voice experiences that we’ve created for now and the ones that we will focus on are ones that are not dissimilar in terms of being useful for the consumer. One of the first apps that I got on my smartphone was a Carling one which was called iBeer and you could use the gyro inside the phone to basically drink a fake beer. The lifespan of that app on my phone was pretty cool for about five days or a week and it was deleted as I wasn’t get much out of it. That is the kind of contextual thinking that we apply to voice and how effective could it be.

We pose a really simple question to clients during our workshops – if your brand had a voice what would it say and why would it say that? What’s the benefit from a consumer’s point of view? In the case of Flight Centre it’s to get the cheapest flight. It’s pretty simple. It doesn’t need to be overcooked. We could do a lot more in that space but what we’re trying to do is build brand but also build consumer adoption.

As an example, there’s a skill our partners Rain have done in the US for Tide. It’s a really smart way of producing a voice experience. If you think about it from the consumer’s point of view, why would they have a relationship with a laundry powder? What would be the benefit for them? What the Rain team developed was a skill that let consumers ask how to tackle stains for example ‘how do I remove coffee from my shirt’.

There’s another great example by Gimlet Media and Crest toothpaste in the US which is called Chompers. They created a really clever way of engaging with children but also reducing a bit of friction with parents. When you launch Chompers in the morning the child gets to listen to the first two minutes of a story while they brush their teeth and then in the evening they get the second part of the story. So, there’s a reason for them to come back to the platform again. It’s that gamification theory which I think is very clever. It’s tapping into an entertainment play but also a utility play at the same time.

How important do you think it is for brands to be thinking about voice?

If voice is not in your roadmap, or at least it’s being considered, then it’s a massive opportunity missed. There’s huge amounts of data to indicate where voice is going to be and also where it’s at now. Recent data shows that 5% of Australian consumers have got a smart speaker in the house and we’ve only had smart speakers in Australia for nine months. Canada which has had them for years is sitting at 7%.

What we’re saying to brands is you can’t ignore the data and if voice is not part of the conversation within the business it absolutely should be. There’s also opportunity for brands to be there first especially in Australia because it’s newer here. It’s a bit like the early days of domain name registration. We have a really popular website here which is called carsales.co.au. It’s pretty obvious from the domain name what the actual website does. What we’re saying to clients is there’s definitely an opportunity to own the invocation names.

With Flight Centre we could have created the cheapest flight skill, but what we decided was that there is a massive opportunity to own cheapest flights via a branded experience. What we ended up with was ‘ask Flight Centre what is the cheapest flight’ so there’s that opportunity to become associated from a brand perspective with what the actual skill or voice experience does.

The other component as well from a brand perspective is owning that headspace early on. You can front-foot it and be that brand that is there before other brands and owning that association. It really should be part of the conversation in terms of the marketing mix and it also should there should be an allocation for something like voice in the marketing spend.

Are there brands or sectors that this is never going to apply to?

It may not suit absolutely every single brand. There’s a role for certain verticals and for brands to be present using voice. We’re not necessarily seeing one vertical or types of brands that are eclipsing others in this market. But Domino’s, for example, absolutely position themselves globally as an innovation organization, so for them part of it was really just speaking true to their heritage. They definitely wanted to be there before another competing brand like Pizza Hut, for example, came into that space. It was definitely a first-to-market play. But we’re still finding there is massive opportunity for other brands to be there, so there’s no reason as to why Pizza Hut should not be in that space as well. There’s absolutely an opportunity for them to be present because again it’s a sales channel.

Whereas I’d say something like our work with Village Cinemas is quite unusual in the sense that that project was initiated by marketing and funded by IT to solve a customer service problem. We produced a voice experience that did two things – tell people the times of films and where their closest cinema is. Off the back of that there’s a transactional component. As a user you can elect to have that information received by your mobile phone as a link and then you can purchase the ticket through that. There’s a commerce component to the project, but it doesn’t transact via voice as such and that’s quite deliberate. They’re mindful of security concerns around commerce transactions done with voice at this point in time.

It was interesting as we identified through the workshops that there was a lot of outbound expenditure for things like the call centre. When Village Cinemas advertises they need to be able to let people know what time a show is on. Someone like my father who’s 73 and inherently just by habit goes to the backpaper of a broadsheet when he wants to see when a film is as that’s where we advertise cinema session times in Australia. He may also be inclined to find out exactly when gold class is occurring, and he might do a transaction on the phone. So, then it becomes a manual intervention for someone like him to be able to call the call centre.

If you think about why a voice experience is quite useful for Village as an example, and this will relate to a lot of other organisations, is you can think of it as being a cost saving. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a revenue generating thing, but rather you can consider what your bottom line is. In the case of Village theoretically if the voice experience means they’re advertising less in broadsheets that’s a cost that’s being reduced for the business. The other aspect is if you think about people in the call center you could theoretically reduce the cost of the overhead and ancillary costs.

Voice definitely has a role to play in being able to save organisations money. There’s also automated analytics as well, so you can generate some really interesting insights off the back of what people are saying or conversely not saying. Instead of some manual intervention, having a live dashboard is highly effective as a means of being able to understand what an audience base is doing or not doing. This may influence things like product roadmaps or ways to communicate to audiences or even things like naming convention.

How are you able to measure the results of voice experiences?

Success is measured in very different ways depending on the experience and we determine those KPI’s with the client. We can look at the total user base that is utilising the voice experience and where they’re going through in the conversational flow and is there a particular drop-off point? What we can’t do at this stage, as there’s a privacy issue around it, is see the very specific questions that are coming in.

Amazon do provide insights, if for example there is a particular word that’s coming up that’s an anomaly that needs to be considered then the dashboard enables us to see what that anomaly is and then be able to rectify that. So, we might want to factor that word into our voice experience if that’s the right thing to do.

The other thing is we may need to cater for a particular word or phraseology in the experience. They call it the pink elephant check. Amazon really like having unusual questions fired at the experience that are abstract and completely unrelated and we then have to make sure that the voice experience can handle something weird.

Can you get aggregate data about what people are asking for?

We are able to get a broad understanding about how many people ask for things. For example, with Village Cinemas we understand that people have asked for a cinema, but there are degrees as to how detailed you can actually get in terms of the analytics. If there’s something we haven’t catered for and it gets asked for multiple times, then we see that because that then makes the experience better from the consumer’s point of view as we get the opportunity to change the voice experience to cater for that variable. But we don’t see all the specific information and that’s mainly because of the privacy issues. That may change and it may evolve as consumers become more used to the platform.

What are the biggest barriers to wider adoption of voice?

The big thing that we found initially was context. If you think about where voice is traditionally utilised, are you really going to talk into your phone on the tube and ask ‘hey Alexa where’s my shopping?’ The context just doesn’t really suit physically where you are.

It’s the same as when Microsoft released Cortana. If you think about a day in the life of someone sitting at work, if I’m shouting at my computer someone thinks I’m drunk or mad or somewhere in between. Context has a massive role to play as to where voice is going to be best utilised.

The other aspect of adoption is finding the personal use case. We tend to say to people is that if you haven’t really played around with one of these devices then the easiest thing to do is go and get one and see how it can be used.

What are the main opportunities for commerce via voice?

Because it’s devoid of a screen, from a consumer’s point of view it probably makes more sense to use voice for repeat orders or more generic purchases. One of the most popular items that does get sold from a v-commerce perspective is batteries. In the case of the US it’s more than likely probably an Amazon branded battery.

The concept of commerce within a voice environment depends on what you’re trying to sell. If you’re looking to sell quite a complex or expensive product or service, there does tend to be that manual intervention at the end. In the case of Flight Centre it’s a gateway to commerce. We do know that to get someone over the line and make a considered spend like an airline ticket you probably do want to have some level of manual intervention off the back of that. That’s partly because the platform is new, but also there is a trust component.

If you think about the early days of ecommerce you might have thought ‘do I really want to spend $100 on a sweater and I’ve never seen it or touched it or smelt it’ and we’re now really ingrained to do that. It’s not even a considered purchase anymore – I trust the brand, I trust the platform and I trust the payment mechanism. There are some similarities around consumer trust for voice.

Security is definitely a consideration. That’s why if you think about the voice experiences that exist in financial services you can’t at this stage shift $10,000 from one account to another by voice. People do like to see visually what they’re doing. There’s also the multi-modal experiences, which are things like the Echo Spot or the Echo Show. That’s the new frontier.

We’re also trying to genuinely help people to reduce friction and to make their life a little bit easier with voice. We created an experience for a brand called Coastalwatch. It’s been around for 10+ years and is a paid subscription for your keen surfer which gives you a live webcam of the surf. What we’ve done is bring this to life with voice. It started as a skill so you can ask Coastalwatch what’s the surf is like at a certain location and it will give you a voice response.

It taps into an API to elicit that result so you get scientific information, but we’ve put language around it to create a tone of voice which is very much Coastalwatch and suits its audience base. In the case of the multimodal experience, so the Echo Spot for example, what that then does is gives you a visual representation of other metadata that you might be interested in. If you think about why multi-modal is interesting, yes it can give you that visual representation, but it also can give you information that may not be catered for in voice.

But the big thing that Amazon is very particular about is it’s always going to be voice first. Even though there might be a screen in front of you the way that we build is that it’s purely based on voice and a visual accompaniment is exactly that. It’s just a way to accentuate the experience. It doesn’t replace voice.

Do you see voice for commerce being integrated into TVs and other screens already in the home?

Have you seen Amazon’s Fire Cube TV? It’s basically the Fire Stick, but it’s actually meant to live in the lounge room like where an Echo would be. The advantage is you get additional content being displayed on screen from the device. The other advantage that it’s got as well is it’s tapping into home automation as well which is quite interesting.

It has an infrared repeater, so you can connect it to your non-smart devices like your stereo and set-up a routine. So if you say ‘Alexa I’m home’ it might dim the lights, it might switch the television on, it might switch Sky TV on to a certain channel. In theory you could say ‘Hey Alexa what’s the best restaurant near me’ and bring up results visually on the screen at the same time. That’s pretty cool and it’s not multi-modal in the sense that you can touch the screen, but you get visual stimulus.

Another thing to reflect on is Amazon are not in the business of making products. Their core business is delivering their ecommerce business. The fact that they’re coming up with different devices is really to test what may land in market and see how people engage. Then you’ve got all the other brands that tapping into the smart speaker market and of course IoT. At the moment, there are 1,400 brands globally that have indicated that they will have Alexa baked into their product line-up. Off the back of that there is meant to be about 4,000 products that that relates to.

We’ve been focusing mainly on physically produced speakers from two organisations (Amazon and Google), but there’s just so many different ways that voice is going to live in our lives. Alexa is very different from Google in the sense that it’s effectively a software layer that can live in a bunch of different things, theoretically anything from a sweater to a photo frame. Google Assistant at this point in time is baked into the physicality of their product line-up, so you can’t necessarily rip out Google Assistant and drop it somewhere else.

Are you having to take Google Duplex and new developments like that into account?

It’s definitely a consideration but not at a commercial level just yet. It’s very much in the early stage of beta. We’re mindful of it, but in terms of having a role to play in our world with our clients in this market it’s too far away at this point in time. The other thing that I think hasn’t really been bench tested with that is that creepiness factor. If you look at some of the comments some people are like ‘that’s so cool’ and some people are like ‘oh my gosh the robots are coming’. In some respects, we have to be so careful with how voice can be amazing. The natural language processing and the computation that’s available now for us to deliver and elicit really good results is getting to that point where it could be considered to be creepy. The thought leaders in this space are being very careful around how they deliver it.

I think personally that Amazon is very particular on Alexa not being too creepy and that’s why her voice at this stage still does sound like a computerised voice. You’ve probably heard the stories though of Alexa laughing unprompted and when the friend got sent a voice recording. From what we can understand they’re super super isolated based on device penetration versus the errors that have occurred. But people don’t want that. Then you don’t trust the robots anymore and people back off from the tech.

The reality is if you think about things that were maybe a little bit creepy one or three or five or ten years ago there’s a lot of stuff in our life now that is now pervasive and we use it. I think voice is probably going to be one of those things but it’s very much like an agile software development methodology the way that they’re building stuff out. It’s the way that we approach it as well for delivering voice.

What is next for VERSA?

Domino’s have been a terrific client for us in the sense that we’ve started with delivering the Australian voice experience for Alexa and that’s now evolved. It’s flipped into Google and also into a multi-modal experience on the Echo Spot. It’s also enabled us to go around the world because Domino’s obviously have got offices in different locations. We’re doing some work with France and Germany and some other territories globally as well. While we’re based in Australia we’re building out projects at a global level. The future is definitely global and also looking at ways that we might be able to productise the offering in other markets.